People think skating, they think California with the beach and these big ramps. They think, maybe, New York with all the street skating. New Orleans’ skate scene is different. Unless you’re looking for it, you don’t really see it.

In the Field: Boarded Up

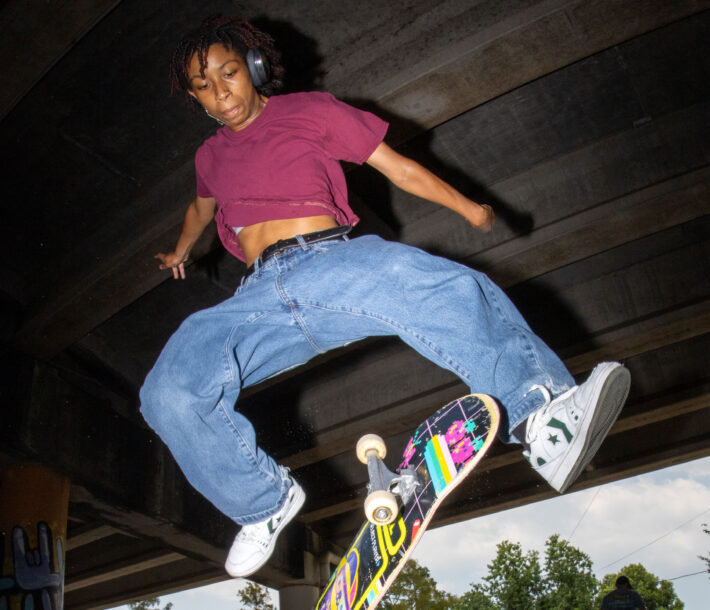

Go behind the scenes with "Boarded Up" filmmaker Mathieu Alexander. Photography by Irvin Washington.

The skate scene in New Orleans is hidden in plain sight.

That’s how Irvin Washington describes it. The 23-year-old says he didn’t see skateboarders in New Orleans when he was growing up in the city. Now, it’s like birdwatching, he says, in that you have to know what to look for. Once you start paying attention to the signs—the ramps set up in the shade, how an alleyway amplifies the sound of a board scraping on pavement—you realize skateboarding exists in places you’d never noticed before.

Irvin is one of the skateboarders featured in a short documentary made by Mathieu Alexander: “Boarded Up.” The project began as a look at skate culture, at large, in New Orleans, but the story led Mathieu and the team to an overlooked slab of concrete under a highway overpass. What was once a no man’s land of concrete columns and rubbish is now built out with quarter pipes and halfpipes, ramps, ledges, and rails—and people of all ages and backgrounds having a good time on skateboards: Parisite DIY Skatepark.

In a city that once lacked a place for skateboarding, Parisite is the keystone propping up New Orleans skate culture, allowing it to flourish. Murals are painted on the concrete towers holding up the overpass. Graffiti adorns the rest. Moveable skate features allow local skaters to transform how the park is set up. It became known as Parisite because of its location, wedged between Paris Avenue and the railroad tracks. But obviously there’s a play on words, with the original skaters embracing the disdain the public once directed their way.

The quarter pipes and bowls are just at the surface of the deep work that’s been done here. The park was built by and for skaters in 2008, one bag of cement at a time. And then, in 2012, the city sent bulldozers to tear it down. Undaunted, two weeks later local skateboarders set out to rebuild the park, and this time they went to City Hall to convince the city’s leaders that skateboarding not only deserved a sanctioned place in New Orleans, but that skateboarding and skate culture also contribute to a vibrant, positive, and creative community.

Parisite is just trying to help the community, the city and pretty much the world understand the benefits of skateboard culture.”

Skate culture builds mental fortitude, Johnny says. Everyone at the skatepark, whether they’re seasoned pros and beginners, is working on progression, developing new skills, challenging themselves physically and creatively. The adversity you encounter on a skateboard opens a door to camaraderie. “Through skateboarding, you find a lot of similarities and friendships,” he adds.

In college, some friends invited Irvin to go skateboarding at Parisite. There, he found a collection of people that he says is unlike any other he’s been a part of, with diversity across race, gender, and age. Young and old. Men and women. Mothers and fathers and brothers and sisters. At Parisite, construction workers getting off work skate in neon vests. He’s met artists, engineers, FedEx workers, bus drivers, and college music professors. “It’s like gumbo,” says Irvin. “There’s so much stuff that goes in a bowl of gumbo. You have the sausage, rice, shrimp, different seasonings. And that’s how skating is. There’s so many people from so many walks of life.”

Because Parisite is an amalgamation of experiences and viewpoints, a lot of stories have been told about the place: a professional skater drops by New Orleans with a film crew or a journalist covers the talks between skateboarders and city officials. There are also the stories that people believe without getting to know a place first. When Irvin first started skating at Parisite, his parents wondered about his safety—the skatepark is located in a neighborhood that has a rough reputation. But as a skater, Irvin met other skaters and realized that Parisite is not what outsiders think. At Parisite Irvin found people who are passionate about moving through a space on wheels and finding a creative outlet in that movement.

“That pushed me into my whole artistic journey and talking about the skate community, especially in New Orleans,” Irvin says. “Because people always have this judgment on and assumption of what they think this place is.”

The filmmakers behind “Boarded Up” took a similar approach. Instead of relying on tired assumptions, they chose to let history stand and went looking for a new angle. They did this by talking to people. In this case, focusing on the stories of some of the Black skaters like Irvin who often ride at Parisite and have played key roles in securing Parisite’s future by working with city government officials. Mathieu, the filmmaker, wasn’t interested in a documentary that capitalized on Black trauma, he says. Instead, he wanted to focus on the experience. “Why they love what they love,” Mathieu says.

Mathieu moved to New Orleans in 2019 when he enrolled at Dillard University’s film program on a scholarship. The university is located across the street from Parisite. Shortly after he arrived at school his Freshman year, he went on a walk in the neighborhood and saw the skatepark.

At Dillard, Mathieu says the program was hands-on. “Shoot whatever you want to shoot. Make whatever you want to make. I really appreciated the freedom,” he says. There, he learned how to execute his vision behind the camera with a student budget, an approach he calls guerrilla auteur filmmaking. “Even though I don’t have the resources to make a perfect aesthetic every time, you will know what my films look like, what my films feel like, regardless of what I have access to,” he says.

When he came up with the concept for “Boarded Up,” Mathieu was inspired by explanatory shows hosted by Bill Nye the Science Guy or Neil deGrasse Tyson. He also wanted to create a film reminiscent of MTV in the early 2000s. Mathieu used to watch those MTV shorts with his uncle and he was keen enough to realize that it took an artist to deliver what the viewer sees as an authentic depiction of a time and place. The intention with “Boarded Up” was to bring it to life and celebrate what makes it tick. “I didn’t want to focus on the narrative that ‘if not for the skate park these guys would be in trouble,’” says Mathieu. “I wanted to get across the simple joys of skating and community. Like, let’s go to Parisite and let’s ask all these people questions and let’s find out what the heart behind this place is and how it got here.”

In this case, it helped that Mathieu isn’t a skateboarder but a self-described “theater kid.” He came to the skatepark curious, with a beginner’s mind, and spent most of his time listening to the stories that create a culture. When he was shooting, he’d show up at the park at 10 a.m. and he’d watch people skate until finally, in the afternoon, they’d sit down for an interview.

He wound up collecting hours of footage and interviews, recording story after story about this place told by the skaters themselves. “Boarded Up” spotlights the positive and the beautiful at Parisite, not the rare tragic incident featured in the news. It’s another layer of storytelling that skaters like Irvin hope will allow people to see the true nature of skateboarding in New Orleans, as a community-driven sport.

“Even though everyone’s story was different, it was cool to see that the common denominator was, ‘This place has helped me in so many ways,’” says Louise Simmons, a fellow student of Mathieu’s at Dillard’s film program who helped film “Boarded Up.” She came to the team with documentary and journalism experience. She’s also a skateboarder. During her freshman year of college, a friend gave her a skateboard and she became a regular at Parisite. Other people in the skatepark would give her pointers, telling her the smallest adjustments made the biggest differences.

“There was a lot of support from the skaters around me,” Simmons says. Once she started skating, she didn’t stop. “Not only just skating at the skatepark, but just skating around the city in general. New Orleans is beautiful.”

When Mathieu sought Louise’s help on the film, she was all in. The experience allowed her to dig in deeper to a place she already loved, and she learned a lot about the backstory of the park that she didn’t know before. “It was such a big question whether they would allow it to keep going and I’m really glad they ended up realizing that it was an important part of the community,” she says.

One cold day at Parisite, Irvin rolled up to a fire roaring inside a barrel. Skaters were warming their hands between laps around the park. Then someone had an idea to use the fire as its own feature. Irvin had stepped away to go to his car, and when he came back, he saw people launching tricks over the flames flickering from inside the barrel.

“Roller skaters jumping over the fire. Skaters doing kickflips, frontside flips, all that type of stuff,” he says. “They were having the time of their life. It was cool to see girls, guys, everybody launching over this blazing barrel.” —Irvin Washington

“We just want to keep being that platform for people,” he says. “That’s the real end goal, to have that relationship with other creatives and just be able to showcase and platform all these things that happened through the skate community.” —Johnny Brasley

Irvin shot a few photographs of the fire session—he majored in art at Xavier University of Louisiana and he’s a photographer. His work aims to change people’s perceptions about skateboarding, so they can see it as Irvin sees it, as a welcoming and creative community. “That’s one of the things that made me really be like, yo skating is one of the coolest things I’ve ever seen,” he says.

By making Parisite a welcoming, safe, inclusive place for skaters, Johnny at Transitional Spaces hopes to open the door for other subcultures to flourish as well. Transitional Spaces works with graffiti artists and muralists to bring art to Parisite, beautify the pillars underneath the highway overpass, and paint skate features. Johnny hopes the skatepark can be a staging ground for not just skateboarders, but also musicians and culinary professionals.

When Louise approached skaters for the film, she says many of them were eager to share their stories and experiences at Parisite. Skateparks offer up organic ways to meet people from different backgrounds. It’s also a space that’s free to come to, something that’s hard to find. “We had so many different angles coming at us, so many different perspectives,” she says.

You really don’t need a lot to tell a really great or powerful story. There’s no huge budget. We didn’t have a huge crew. It was a very guerrilla style of shooting it. But we still were able to tell a powerful story. —Louise Simmons, filmmaker.

One of the points of view they decided to include was Irvin’s, whose love for skateboarding feels contagious.

“All you need is a board. That’s it and you can go all day,” Irvin says. “There’s no right or wrong way to skate, in my opinion. I see it as the most free form of sport that there is. You can do ramps, you can do rails, you can do stairs. You don’t have to do any of that. You can freestyle. You can do hand grabs. You got guys flipping, guys doing handstands with the boards. I think that’s the coolest part of skating, to be honest, the fact that it is so creative. It’s like painting, like art.”